Racine at the Girls' SchoolWritten for the Cheltenham Ladies' College to perform at the Cheltenham Literary Festival of 1992 this play was performed entirely by girls, mostly sixth-formers. Bryan Robertson in The Spectator: "Spurling paid the College the compliment of writing a serious, highly entertaining play of ideas and this confidence was repaid handsomely by a production better acted and better-looking than many dismal affairs seen in London." The subject was one that had been at the back of my mind for many years. Racine's last two plays - Esther and Athalie - were partly operatic Biblical stories written for Madame de Maintenon's new girls' school at St Cyr and performed entirely by teenage girls. Why, after his masterpiece Phèdre, did he write no more plays for ten years and never again for the professional theatre? My research provided the answer, which this play incorporates. But I soon became still more intrigued by the circumstances of the actual production of Racine's Esther in 1689. Although the subject was deliberately 'improving' - the school had previously mounted an alarmingly passionate version of Racine's early play Andromache and Madame de Maintenon had asked for something very different - there was powerful opposition from some quarters to the whole project and especially its popularity with the Versailles courtiers. At the fourth performance, on February 5th, 1689, Madame de Maintenon's niece, Madame de Caylus, took over the name-part and sent the audience into raptures. Among the audience on this occasion were the exiled King James II of England and his Queen. The following day, February 6th, back in their lost kingdom, the English Parliament confirmed the so-called 'Glorious Revolution' of 1688 and inaugurated the British system of constitutional monarchy by bestowing the throne on James's daughter Mary and her Dutch husband, William. They are known to history as our only joint monarchs: William III and Mary II. The "turncoat" general John Churchill, who helped bring William and Mary to power because he feared that James would make England Catholic again, later became Duke of Marlborough and won many decisive victories against Louis XIV's armies, frustrating his attempts to dominate Western Europe. John Churchill's most famous descendant was, of course, Winston Churchill, who did so much to frustrate Hitler's attempt to dominate Europe in the 20th Century. As if all this weren't enough, I discovered that the schoolgirl playing the part of Elisa in the play - her name was Marie Clara des Champs de Marcilly - went on to marry the Marquis de Villette, one of the eager courtiers who saw her perform and was himself a cousin of Madame de Maintenon. I'm not sure of his exact relationship to Madame de Caylus and, for simplicity's sake, have called him her brother. However, since I'd tied myself down - emulating Racine's own classically-structured plays - to Aristotle's 'dramatic unities' of place, time and action, I was unable to use the rest of Mlle de Marcilly's story. After the death of her husband, the Marquis de Villette, in 1707, she married again. Her second husband was the exiled British politician, Henry St John, Viscount Bolingbroke, and the couple eventually retired to Bolingbroke's family home in London. They died in 1750 and 1751, are buried together in the crypt of Battersea Parish Church in South London, and commemorated on the wall of the church in a marble relief by the famous sculptor Roubiliac. I suspect that the Marquis de Villette was older than I've made him, but felt that, in a play for 17-year-old girls, I already had enough middle-aged gentlemen in the cast. I have also taken some dramatic licence with the Jansenist heresy issue that emerges in the latter part of the play. Everything here about Racine's connection with the Jansenists - and Madame de Maintenon's with the Protestants - is historically accurate. But Racine did not fall foul of the King's prejudice against Jansenists until several years after Esther. The Bishop of Chartres' interpretation of Esther is mostly my own - as is that of Madame de Caylus - but whether there really is some hidden political/religious meaning in the play is still an open question and people at the time certainly read real persons into the characters, as Racine's enemies do in my play. The Curé of Versailles' fierce opposition to the girls' performance of Esther is entirely historical, though I have provided him with his arguments. The translations from the spoken text of Esther are my own, but in the first production we left the sung parts in French. It fits the music better than a translation could and sounds more ethereal than English. When we first began work on RACINE AT THE GIRLS' SCHOOL we thought that the music director of Cheltenham Ladies' College, John Wright, would himself have to compose music for the sung parts in the style of the period, since nothing but a small harpsichord piece by the original composer, Jean-Baptiste Moreau, seemed to have survived. Then we discovered that the British Library owned a copy of the complete score for Esther. So John Wright edited and transcribed the sections I wanted for my play and Moreau's music received what may well have been its first ever hearing in England. A shortened version of this score was used again for the play's second production, by St Paul's Girls' School in London, in 1993. There is to this day no evidence that Louis XIV, after the death

of his unhappy Queen in 1683, actually married Madame de Maintenon, who

had been employed to look after his illegitimate children by a previous

royal favourite, Madame de Montespan. But all historians are certain that

the marriage did take place, probably in the same year as the Queen's

death. Given the strong moral pressure Madame de Maintenon exerted on

the King and the moral 'cleansing' that took place at Versailles once

she became 'first lady' - including her foundation of the St Cyr school

for the daughters of poor noblemen - the historians are surely right. The words of the 'loyal song' written by the Headmistress of St Cyr, Madame de Brinon - the original music by Lully is lost - may seem oddly familiar. Nancy Mitford's popular biography of Louis XIV - The Sun King - prints the French text of this prototype of the British National Anthem as well as illustrating the exact school uniform worn by the girls of St Cyr. Adapted by Judy Langhorn, it looked so good on the Cheltenham Chorus that I began to hope the Ladies' College might think of replacing their own in its favour. The principal characters' costumes were also made specially - by Michelle Walton - and were equally authentic, not just to the period in general, but to the year 1689. The ex-Queen of England, James II's second wife, is usually called Mary, but this is confusing, since her step-daughter, the usurping Queen of England, was also called Mary. In any case, the ex-Queen was Italian, daughter of the Duke of Modena, so on both counts she's better called Maria. The baby she refers to was called James and grew up to be 'The Old Pretender', father of 'The Young Pretender', Bonnie Prince Charlie. |

Racine at the Girls’ School: Justine Levy as Madame de Caylus and Madeleine North as Racine

|

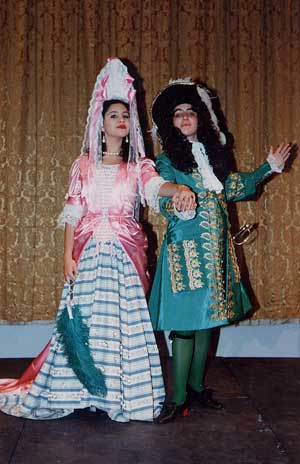

Victoria McAtamney as King Louis XIV and Philippa Yates as King James

II

|

Justine Levy as Madame de Caylus in Racine at the Girls’ School

|

Chorus of the girls of St Cyr with Jean-Baptiste Moreau and his assistant

|

Alex Btesh as Queen Maria and Philippa Yates as King James II

|